University of Chicago and Cornell University researchers analyzed wearable health care electronics and reported carbon impacts of 1.1–6.1 kg CO2-equivalent per device. With global device consumption projected to rise 42-fold by 2050, approaching 2 billion units annually, their moderate projection adds 3.4 million metric tons of CO2-equivalent emissions alongside ecotoxicity and e-waste.

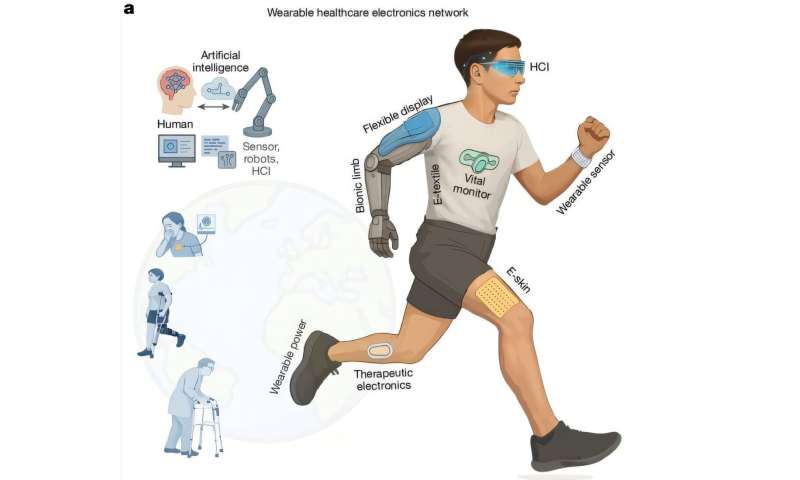

Wearable electronics—glucose, heart and blood pressure monitors, integrated into patches, chest straps, clothes and smartwatches—are transforming health care through real-time monitoring, device interaction, and therapeutic interventions.

Compared with rigid consumer electronics, wearable health care systems—ranging from biophysical and biochemical sensors to e-textiles and biointegrated therapeutics—offer high compliance and continuous tracking and intervention capabilities.

With wireless integration, wearable health care electronics are evolving into digital infrastructure networks adopted globally by patients, older people, athletes, and health-conscious people.

Reliance on energy-intensive manufacturing, hazardous chemicals, fossil-based plastics, and critical metals can lead to substantial carbon emissions, ecological risks, and e-waste issues. Rising energy demands from artificial-intelligence-driven data processing and advanced digital infrastructures further enlarge the eco-footprint of even the smallest devices.

Searching the sustainability blind spots

In the study, "Quantifying the global eco-footprint of wearable health care electronics," published in Nature, researchers integrated life-cycle assessment with forecasting adoption growth over time to quantify global eco-footprint hotspots and evaluate mitigation strategies.

Four devices anchored the assessment—a non-invasive continuous glucose monitor, a continuous electrocardiogram monitor, a blood pressure monitor, and a point-of-care ultrasound patch. Selection criteria included clinical relevance, diversity of sensing modalities, and coverage across an expanding technology spectrum.

Cradle-to-grave attributional life-cycle assessment covered raw-material acquisition, manufacturing, transportation, use, and end-of-life disposal. Monte Carlo simulation quantified uncertainty for environmental impacts, and diffusion modeling projected future scale of use.

Butterfly effect of small devices becomes a torrent

A single continuous glucose monitor from production to use carried a carbon footprint equivalent to about 2 kg CO2-equivalent, or driving a gas-powered car for around 5 miles. More than 95% of that impact was attributed to printed circuit boards and semiconductors inside the device, tied to energy required to purify raw materials and power manufacturing processes.

Single glucose monitor use lasted 14 days before being discarded and replaced. Repetition of that short cycle has stacked impacts across the scale of users. Wearable glucose monitor sales are estimated to exceed 1.4 billion devices a year by 2050.

Expected greenhouse-gas emissions from these units alone were around 2.7 million metric tons CO2-equivalent annually.

Per-device warming impacts ranged from 1.06 kg CO2-equivalent for a blood pressure monitor to 6.11 kg CO2-equivalent for a point-of-care ultrasound patch. Values of 1.30 kg CO2-equivalent for a continuous electrocardiogram monitor.

Annualized warming impacts, accounting for typical replacement frequencies, were 0.5 kg CO2-equivalent for the blood pressure monitor, 33.8 kg CO2-equivalent for the continuous electrocardiogram monitor, 50.6 kg CO2-equivalent for the non-invasive continuous glucose monitor, and 6.1 kg CO2-equivalent for the point-of-care ultrasound patch.

Greenhouse-gas emissions from all wearables in the model were 3.4 million metric tons CO2-equivalent annually, or about the carbon footprint of the transport sector of Chicago. Component-level analysis placed flexible printed circuit board assemblies at the center of warming impacts across all four devices, with hotspots tied to gold in integrated circuits, silicon wafers, polyimide, and batteries.

Design choices with outsized payoffs

Researchers modeled four mitigation approaches that included plastic substitution or recycling, critical-metal substitution, modular designs for reuse and replacement, and a transition to green energy.

Biodegradable or recyclable plastics produced small reductions in warming impacts, with reported changes of 1.8–2.6% for the non-invasive continuous glucose monitor under cellulose, polylactic acid, starch, and 100% plastic recycling scenarios, plus theoretical 100% recycling reductions of 2.6–7.7% across device types.

Dominance of flexible printed circuit board assembly across wearable footprints made polymer-focused gains inherently limited.

Critical metals and device design levers carried larger shifts in modeled outcomes. Substituting gold with silver, copper, or aluminum in integrated circuits reduced warming impacts by up to about 30% and cut toxicity-related metrics by more than 60% for freshwater ecotoxicity and non-carcinogenic human toxicity.

Modular designs with pluggable interfaces allowed reuse of long-lived circuits while replacing high-turnover parts, reducing per-use warming impacts by 54.6–62.4% across three device types.

Transition to renewables-intensive electricity by greening the power grid source itself reduced overall warming impacts by 44.9–52.1%, while ecotoxicity and water consumption showed negligible improvements, a pattern that left decarbonizing electricity alone short of full mitigation.

Systems engineering linked with life-cycle assessment and diffusion modeling showed promise for establishing ecologically responsible innovation in next-generation wearable electronics.

Written for you by our author Justin Jackson, edited by Sadie Harley, and fact-checked and reviewed by Robert Egan—this article is the result of careful human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive. If this reporting matters to you, please consider a donation (especially monthly). You'll get an ad-free account as a thank-you.

More information: Chuanwang Yang et al, Quantifying the global eco-footprint of wearable healthcare electronics, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09819-w

© 2026 Science X Network

Citation: The hidden carbon footprint of wearable health care (2026, January 5) retrieved 5 January 2026 from https://techxplore.com/news/2026-01-hidden-carbon-footprint-wearable-health.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.